By Peter C. Vermilyea

Department Chair and History Teacher

Housatonic Valley Regional H.S. & Western Connecticut State University

Getting students interested in, let alone excited about, some of history's most important people and events can be challenging. For years, Peter Vermilyea, Department Chair and history teacher at a Connecticut high school, has been overcoming that challenge by infusing local history into the curriculum. Read on as he details how an amazing discovery of long-forgotten treasure chest served as the impetus for a customized, six-years-and-running history project that has students excited to learn about their community while building their skills.

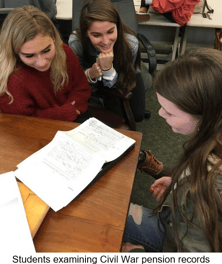

Our project began with a scene more likely to be found in an adventure movie than a high- school history classroom. A new colleague, setting up his classroom appeared at my door with an actual treasure chest, something found in Pirates of the Caribbean. “I found this in my closet,” he said. “You might be interested in it.” Opening it, I found the detritus that most history buffs accumulate over the years: brochures, pamphlets, those reproductions of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution. At the very bottom of the chest, however, was the history teacher’s gold -– pension records for five African American Civil War veterans who had once lived in our school district.

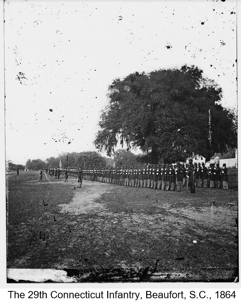

These men served in the 29th Connecticut Infantry, an all-Black unit raised in the winter of 1863-64 in response to the growing manpower needs of the Union Army. Its members came not only from Connecticut but also from other Northern states that did not have Black regiments of their own, as well as 265 men who had once been enslaved in the 11 states that seceded. Trained in New Haven, the 29th Connecticut served in Maryland, South Carolina, Virginia and Texas in 1864 and 1865. At the Battle of Kell House, Virginia in October 1864, the 29th suffered 80 casualties. On April 3, 1865, the regiment earned the distinction of being the first Union regiment to enter the Confederate capital of Richmond.

These men served in the 29th Connecticut Infantry, an all-Black unit raised in the winter of 1863-64 in response to the growing manpower needs of the Union Army. Its members came not only from Connecticut but also from other Northern states that did not have Black regiments of their own, as well as 265 men who had once been enslaved in the 11 states that seceded. Trained in New Haven, the 29th Connecticut served in Maryland, South Carolina, Virginia and Texas in 1864 and 1865. At the Battle of Kell House, Virginia in October 1864, the 29th suffered 80 casualties. On April 3, 1865, the regiment earned the distinction of being the first Union regiment to enter the Confederate capital of Richmond.

However, we knew little of this at the time. The story of the 29th Connecticut, like the story of so many other Black units in the Civil War, had largely been forgotten. A brief regimental history recounted the basic facts of the unit’s experience. A memoir by a member provided glimpses of the human experience. But the voluminous newspaper articles, letters, and books that detail the history of most Civil War regiments is missing for the 29th. Because the unit had no hometown, it also lacked a monument until a Connecticut reenacting group that kept the unit’s story alive erected one in 2007 at the site of the training camp in New Haven. Beyond these snippets, the regiment’s story had been shrouded in mystery.

We knew immediately that the pensions at the bottom of the chest offered an unparalleled opportunity for students to roll up their sleeves, do the hard work of historians, and bring the story of the 29th Connecticut to the public. Our question was, what was the best way to do that? We reached out to professors, teachers, and public historians who offered excellent suggestions before we settled on building a website that would tell the stories of the individual members of the 29th in a way that would contextualize the experiences of Civil War soldiers, highlighting those shared by soldiers regardless of their race, as well as those experiences unique to Black soldiers.

From a pedagogical perspective, there were four aspects of this project that were especially appealing.

From a pedagogical perspective, there were four aspects of this project that were especially appealing.

- First, it would require our students to dig deep into the primary sources – pension records, military service records, archival materials, period newspapers – that are the bedrock for historical work.

- Second, such a project would allow our students the opportunity to reach out to experts in the field with questions on their research, sources, and angles that could be pursued.

- Third, building a website that told the story of local Black Civil War soldiers would require our students to collaborate with each other, both within their own history class and with future students who would continue the work in coming years.

- Finally, it has always been our firm belief that students do their best work when they know it is for a public audience.

We had a very large group of students the first year (2017-18) we worked on ProjeCT29 (the name derived from the 29th Connecticut), www.project29.org. These were juniors, enrolled in our dual-enrollment United States History course with the University of Connecticut. The groups would simply have been too large had we divided up the five pension records that were in the chest among all the students, so additional topics were necessary. Having presented a general history of the unit to the students, we asked them what other topics they felt merited research. The students were quick to offer excellent suggestions: an overview of African American soldiers in the war, the background on the regiment’s formation, a history of the regiment with a focus on the battles in which it fought, comparative studies of disease and desertion among white regiments and Black regiments, and an interactive map showing the movement of the regiment.

We had a very large group of students the first year (2017-18) we worked on ProjeCT29 (the name derived from the 29th Connecticut), www.project29.org. These were juniors, enrolled in our dual-enrollment United States History course with the University of Connecticut. The groups would simply have been too large had we divided up the five pension records that were in the chest among all the students, so additional topics were necessary. Having presented a general history of the unit to the students, we asked them what other topics they felt merited research. The students were quick to offer excellent suggestions: an overview of African American soldiers in the war, the background on the regiment’s formation, a history of the regiment with a focus on the battles in which it fought, comparative studies of disease and desertion among white regiments and Black regiments, and an interactive map showing the movement of the regiment.

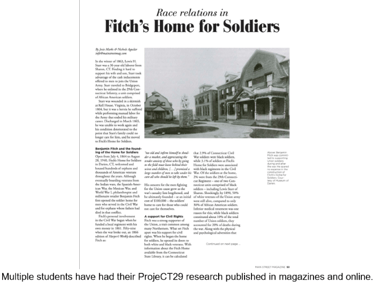

Funding from the 21st Century Fund, a community organization dedicated to supporting special programming for our students, allowed us to order additional pension records from the National Archives. Identifying local veterans and searching for their records at the National Archives became the responsibility of one student per year. Another student each year has served as the editor, ensuring continuity of style, while another student serves as our webmaster. Discoveries from the archives have led to additional thematic pieces being added to the website, including a bounty scandal involving white recruiters embezzling the bonus money of Black volunteers, the difficulties encountered by many African American widows to secure a pension following their husbands’ deaths, and the experiences of veterans living in Connecticut’s integrated soldiers’ home in the post-war years. One of our guiding mantras has been that we will pull at whatever threads we discover and see where the research takes us. It should also be noted that all this work took place within a full United States History survey course; about two days a month were devoted to ProjeCT29 work. ProjeCT29, now about to begin its sixth year, has provided unanticipated opportunities for our students. Upon seeing the website, neighboring schools expressed their desire to do similar work, resulting in a wildly successful three-day symposium on local Black history. Two of our students were asked to speak at meetings of a local historical society and a local community group. Three of our students have had their work published. Our students have worked closely with university professors and authors from across the country, National Park Service historians, and archivists at the National Archives and repositories in Connecticut. ProjeCT29 has helped them become better researchers, better writers, better problem solvers, and better collaborators.

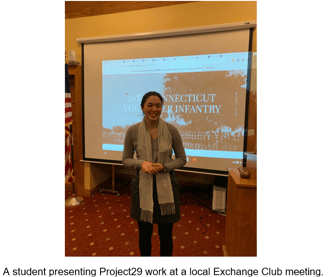

ProjeCT29, now about to begin its sixth year, has provided unanticipated opportunities for our students. Upon seeing the website, neighboring schools expressed their desire to do similar work, resulting in a wildly successful three-day symposium on local Black history. Two of our students were asked to speak at meetings of a local historical society and a local community group. Three of our students have had their work published. Our students have worked closely with university professors and authors from across the country, National Park Service historians, and archivists at the National Archives and repositories in Connecticut. ProjeCT29 has helped them become better researchers, better writers, better problem solvers, and better collaborators.

Our ProjeCT29 journey began with a serendipitous discovery, but every community has important stories waiting to be told, and high school students are well-equipped to research and tell them. An extremely valuable resource for getting started is Chronicling America (www.chroniclingamerica.loc.gov), the Library of Congress’s digital newspaper project. Local newspapers are a gold mine for piecing together past lifeways. Similarly, the Sanborn Fire Insurance maps (www.loc.gov/rr/geogmap/sanborn), also at the Library of Congress, can stimulate student research into their town’s history and provide opportunities for “then and now” comparisons. Most local historical societies are eager to help with student research, and many will bring records to the students if field trips cannot be arranged. University and state archives have been leaders in digitizing their collections. The National Archives (www.nara.gov) houses all military records, including pension and military service files. Copies of these can be ordered online for a fee, but this process has been slowed by COVID. Fold3 (www.fold3.com), a subscription website, offers access to an enormous amount of genealogical material, including many pension and military service records. FamilySearch (www.familysearch.com), a website operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has made historical census information available online for free. These institutions have been of tremendous help, but there is no patented formula for local history projects. That, however, is the real value of such work, for it is in the experience of pulling at those threads that the most valuable student learning takes place.

It seems fitting to end with the students. What have they had to say about this project? First, a disclaimer. They complain – a lot – about the difficulty of reading 19th century cursive. Once they get past that, though, the most common words and phrases they use to describe their experience with ProjeCT29 are: “an opportunity to be the historian,” “we explore the past, not just memorize it,” it generated “enthusiasm for history,” and it is “a much better way to measure my understanding of history than multiple choice.”

These gems seem appropriate for a project that began with a treasure chest.

To learn more, please watch Peter's Hidden In Plain Sight webinar.

Learn how Duval County Public Schools is re-energizing Social Studies with primary and secondary sources that connect students to state and local history.